|

This is the tale of two pencils, each the brainchild of a pioneering inventor. One came from America; the other, from Japan. Twenty years ago, the stories of these two pencils got confused and ended up conflated into a single account, which has been repeated in every book and article on pen collecting published since.[1] According to this thoroughly scrambled history, the Eversharp pencil was invented in Japan by Hayakawa Tokuji, who later went on to found the Sharp Electronics company; rights to this pencil were purchased by the Wahl Company of Chicago, which moved production to the United States.

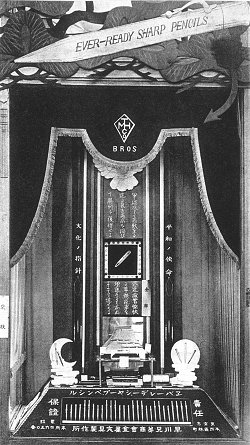

Fig. 1: Hayakawa's Ever-Ready Sharp Hayakawa Tokuji was the founder of Sharp, and he did invent a mechanical pencil in 1915 when he was only 21 years old. It was not, however, the Eversharp. Hayakawa's pencil is now revered as one of the first two milestones in a long career marked by continual innovation and heroic perseverance, and examples are on permanent display at Sharp's corporate museum in Japan (fig. 1).[2] Marketed as the Ever-Ready Sharp pencil, it received Japanese patent #54,357 in 1920, and in 1923 an application was filed for a United States patent which was granted in 1926 as number 1,578,515 (fig. 2). Initial response to the Ever-Ready Sharp in Japan was cautious, but sales began to pick up after Hayakawa landed a substantial export order from a Yokohama trading company, an order whose ultimate destination remains unknown. I have been searching for examples of Ever-Ready Sharp pencils for some years, and my lack of success in finding any in the United States suggests that very few if any were sold here.

Fig. 3: Ever-Ready Sharp display, 1922 The Eversharp pencil was the brainchild of Charles R. Keeran, a native of Bloomington, Illinois and an inveterate inventor and entrepreneur. Nowadays collectors take these seemingly ubiquitous all-metal pencils for granted, yet the original Eversharp was truly a groundbreaking innovation. The first mass-produced mechanical pencil to combine a simple propelling mechanism with large lead capacity and robust, ergonomically sound design, the Eversharp met with enthusiastic public acceptance. In the space of a few years millions were sold, not counting the numerous imitations which soon appeared, virtually all using the .046" (1.2 mm) lead that the Eversharp had established as a new standard. It was the Eversharp that redefined the mechanical pencil as a mass-market product, to the extent that "eversharp" came to be widely used as a generic term for a mechanical pencil.

Fig. 7: Heath-made sterling silver Eversharp, c. 1914 The new pencils were test-marketed over the 1913 Christmas season at Wanamaker's in New York, and reportedly sold well at $2 to $3. Keeran did not want to stay in the East, however, and early in 1914 Keeran & Co. was set up in Bloomington, Illinois to sell the Eversharp (fig. 8). According to Keeran's own account, it took about a year after setting up the new company to get into production, but it is not clear who was doing the actual manufacturing at that time. Since Heath must only have just tooled up a few months before, it seems likely that they continued to supply at least some of Keeran's Eversharps after the move to Bloomington. How many other contract manufacturers were used remains unknown; what seems clear, however, is that Keeran's chief problem was in production, not in sales.[7]

Fig.

8: Charles R. Keeran's business card, c. 1914 In any event, Charles Keeran was not standing still. On October 28, 1914 he applied for a patent on a feature that would remain an Eversharp standard, the "rifled" tip (whose grooves guaranteed a consistent resistance to the passage of the propelled lead), for which patent 1,151,016 was granted on August 24, 1915. Keeran also arranged to have a booth promoting Eversharp at San Francisco's Pan Pacific Exposition, which ran from February to December, 1915. Keeran later wrote that this venture led to the sale of tens of thousands of Eversharps through a San Francisco firm, though it is not clear if these sales were during the run of the fair or over a longer period. In late summer of 1915 Keeran moved his company headquarters to Chicago; in September 1915 the first published advertisement for Eversharp appeared in the magazine Office Appliances, listing the company address as 1417-19 Lytton Building, Chicago. It was not long after that Keeran had his first, fateful contact with the Wahl Adding Machine Company. The initial approach was in hopes of purchasing machinery, but Wahl wanted the work themselves. A contract to manufacture Eversharps was signed around the beginning of October of 1915; production began some two months later at a rate of around 200 pencils per day. There is some disagreement in our sources about what happened next; two lawsuits between Keeran and Wahl were to follow, and examination of the transcripts is now pending. It appears, however, that the Wahl directors saw both the Eversharp's potential and Keeran's lack of capital, and exploited the situation ruthlessly. In mid-November of 1915 Keeran unwisely allowed Wahl to gain control over his company in exchange for an infusion of $20,000.[8] During the following year production lagged, leaving Keeran's company unable to fulfill orders.[9] At the end of 1916 the weakened enterprise was wholly absorbed by Wahl through an exchange of stock, leaving Keeran with but a tiny stake in the combined firm and holding the position of sales manager. Throughout all this, Keeran continued to give the enterprise his all, and in November of 1916 his efforts on behalf of Wahl secured an option to purchase the Boston Safety Fountain Pen Company on exceedingly favorable terms, the acquisition that put Wahl into the pen business.[10] During the same period, he was also acting as a troubleshooter, in one year making twelve trips to New York City "to straighten out patent tangles, etc." Nonetheless, in August of 1917, Keeran was replaced as sales manager and essentially forced out. His resignation was accepted on December 20, 1917.[11] Four years later, Wahl was turning out 35,000 Eversharps every day, and had sold over 12,000,000 pieces. In 1927, Keeran's youngest son underwent emergency surgery for a ruptured appendix. Under financial duress, he accepted Wahl's payment of $2500 "and a few pens" in final settlement for his share of an enterprise that was by then generating millions in profit annually. Charles R. Keeran remained active in the field of pencils, with further patents assigned to companies such as Autopoint, Realite, and Durolite. Yet his role as inventor of the Eversharp and midwife to Wahl's rebirth as a writing equipment company was soon forgotten, in no small part thanks to Wahl's deliberate obfuscation of its own early history.[12] Wahl began making Eversharp pencils on its own account at the beginning of 1917. Eversharps made prior to the takeover are not common, and display a number of distinctive features. Imprints make no mention of Wahl, of course, and "EVER SHARP" appears with a slight gap separating the two words (fig. 2).[13] Gold filled pencils are marked "20 YEAR GOLD FILLED" instead of the simple "GOLD FILLED" found on later examples. Very early pencils may bear imprints on the crown rather than the barrel, and I am aware of at least one pre-Wahl pencil with no imprints at all.

Fig. 9: Eversharp "Trowel clip", c. 1916 There appear to have been only two clips used prior to 1917, of which the pierced-base Heath design was the first. The second was what we shall term the trowel clip (fig. 9), for which Keeran filed a patent application in April of 1916, approved October 10, 1916 as design patent 49,743. While it seems likely that the Heath clip was abandoned at the same time Heath stopped manufacturing for Keeran, the exact chronology remains to be established.[14] Dating of the trowel clip is somewhat more certain, as it appears to have been adopted at the time Wahl first began to produce Eversharps under contract, some months before the patent application was filed. It seems the trowel clip was discontinued as soon as Wahl took over; to my knowledge, no Wahl-marked Eversharps with the clip are known. Its replacement by the familiar flat clip (fig. 10) thus took place right at the beginning of 1917. The patent application for the flat clip was filed by Wahl on March 8, 1917, for which patent 1,279,186 was issued on September 17, 1918.

Fig. 10: Wahl-Eversharp flat clip, c. 1917-24 From the beginning, Eversharp pencils were offered in a wide range of materials and patterns. Materials offered ranged from nickel silver to solid 14K gold. Patterns included the basic engine turned designs familiar from later Wahl-made pencils, as well as various hand-engraved and repoussť motifs not found in later production, such as the floral relief work on the Heath-made sterling pencil shown in figs. 5 and 7. At least one acid-etched pre-Wahl Eversharp is also known. Much research remains to be done on both Keeran's Eversharp and Hayakawa's Ever-Ready Sharp, enough that book-length treatments will eventually be in order. For the present, however, the record has at last been set straight. In many respects, this has been a collaborative effort. For Charles R. Keeran, I am particularly indebted to Robert L. Bolin, whose online publication of the documents now in the possession of John and Jane Keeran was nothing less than groundbreaking.[15] Both Bolin and the Keerans have shared their research with exemplary generosity, as has Boston Safety expert Patricia Lotfi, who first introduced me to the Keeran saga. For Hayakawa Tokuji, the numerous gaps and inconsistencies in English-language versions of his story were finally cleared up through the kind assistance of Hiromi Morita of the Sharp Corporation and the material so freely shared by veteran collector Masa Sunami. [1] Cliff Lawrence's first company history of Wahl-Eversharp was published in serial form beginning in 1979: The Pen Fancier's Newsletter, 2/10 (October 1979), pp. 5ff. An amended version first published two years later attempted to fill in the gaps in the first account, using a confused version of the Hayakawa story: op. cit., 4/3 (March 1981), p. 25. Interestingly, Lawrence later published a pre-Wahl advertisement for Eversharp in An Illustrated Fountain Pen History, 1875 to 1960 (Dunedin, FL, 1986), fig. 226, p. 94, in which Keeran's name is listed as company president and in which the company address, 557 People's Gas Building, is clearly not Wahl's. The date given is 1917, but 1916 seems more likely. [2] For the Sharp Memorial & Technology Hall, visitor information is posted here. The official Sharp company history lists both the first product of the Hayakawa Brothers firm, a metal belt buckle, and the Ever-Ready Sharp pencil. The most extensive Sharp page on the pencil is currently found here (as of March 2009). [3] Outline biographies of Hayakawa Tokuji appear in a number of general reference works on Japan, as well as on the Sharp corporate website as noted above. A recent reference is Bob Johnstone's We Were Burning: Japanese Entrepreneurs and the Forging of the Electronic Age (New York, 1998). For the most detailed account, there is the 1962 biography of Hayakawa; I am deeply indebted to Masa Sunami for providing me with copies and translations from this book, along with various observations from a collector's perspective. [4] Fourth from the left on p. 64 of the 1962 biography. This piece can be no earlier than c. 1932, for its clip has clearly been copied from that of vest-pocket Doric. [5] The main sources for the origins of the Eversharp are in the possession of Charles R. Keeran's grandson, John Keeran. Most were available through Robert L. Bolin's website devoted to the Chicago pencil industry (formerly at http://www.unl.edu/Bolin_resources/pencil_page/keeran/index.htm, archived at the Internet Archive), most notably Keeran's lengthy letter of February 2, 1928. Keeran's account appears to be entirely consistent with the evidence of advertisements, flyers, and the pencils themselves, as well as with the account published by C. A. Frary, Wahl's general manager: "What We Have Learned in Marketing Eversharp", Printers' Ink, 66/6 (August 11, 1921). [6] The Eversharp logo is still an active trademark, #71327611, with first commercial use claimed December 1913. [NOTE: this number is the serial (filing) number for US trademark 297,913 which was issued in 1932, and which was a modification of the original Eversharp trademark, 147,712. Thanks to George Kovalenko for the correction.] [7] Frary states that prior to the arrangement with Wahl, Eversharps had been made "piece by piece, here, there, and yonder." [8] For the original letter, see Robert L. Bolin's website, referenced in note 5 above. [9] Keeran claimed in his letter of 1928 that Wahl had promised to provide 1000 pencils per day during 1916, but only produced 100. This is consistent with Frary's statement that Wahl produced "several thousand" pencils for Eversharp during the same year. [10] Patricia Lotfi is currently researching this along with many other aspects of the history of the Boston Safety Company. [12] Frary does not mention Keeran's name once in either his 1921 article noted above, or in his account of Wahl's entry into the fountain pen business: "Marketing Eversharp's Partner", Printers' Ink, (November 30, 1922), pp. 17ff. These were Cliff Lawrence's two chief sources for the early history of Wahl as a writing instrument maker. [13] Not to be confused with later English-made Eversharps, whose imprints typically omit the Wahl name. Note that the earliest Wahl-marked Eversharps also retain the gap between "EVER" and "SHARP". [14] An unpublished flyer in the possession of John Keeran, bearing the People's Gas Building address, and thus no earlier than the last quarter of 1915, depicts two Eversharps with Heath-style clips. The possibility remains, of course, that the cuts for the illustrations were originally for an earlier brochure, and were being reused. This was a common practice, and one need not look far for examples: the Eversharp ad from c. 1916 published in Lawrence's An Illustrated Fountain Pen History (see note 1 above) shows a pencil with the Heath clip alongside a large sectional view of a trowel-clip Eversharp; this sectional view then reappears unchanged in Wahl's 1919 catalog, this time flanked by an Eversharp with the then-current flat clip (Glen Bowen, Collectible Fountain Pens (Gas City, IN, 1982), p. 194). [15] See note 5 above.

Copyright © 2001 David Nishimura, updated 2013, 2023. All rights reserved |